Journal Entries:

Atlantic Crossing – July, 1943

![]()

At left is a picture of Billy taken during

the crossing, loaned by Mrs. McKenna

|

Journal Entries:Atlantic Crossing – July, 1943

At left is a picture of Billy taken during |

Display map of crossing • Display navigator's log of crossing (PDF file) • Display the orders to ship out

Note: the dates given for these entries are the dates as they were entered into the Journal; the crossing actually took place in July

August 21 — Somewhere in England

So far every mission has been training. We hope to go on operations very soon. The trip over began in Avon Park, Fla. on July 10, '43. We went by train to Savannah, Ga. There we picked up our plane, a B-26 #131863. We didn't name it, but 1863 is a number I shall always remember. She was a beautiful ship, trim and streamlined in every respect, and fast too. With 40,000 lbs. we soared off Savannah's long runways.

|

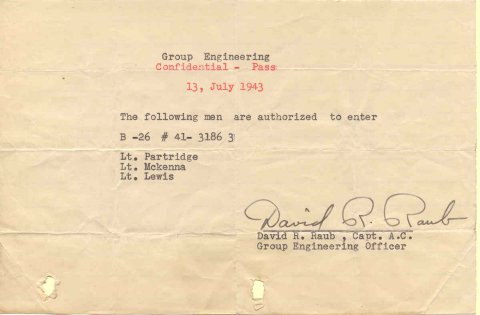

Here is an image of the pass issued to Billy and his buddies as they began their flight to England. [1] |

Our first stop was New Castle, Delaware. We flew direct to Richmond, Virginia and from there we flew airways past Washington, D.C. It was beautiful. It was my first trip to the city and I was so very sorry that we couldn't land. We continued airways past Baltimore, then on across country to the Delaware, then up the Delaware to New Castle Air Base and an important base of the Air Transport Command (Ferrying Division). We spent the night in New Castle on the post and I ran into Harry Anderson, a chum of cadet days. At the time Harry had made one crossing via the Southern route, [2] jumping off from Morrison Field, West Palm Beach. He was preparing for another hop to India. We had a jolly time talking over old times at Hondo. Harry was expecting his first soon.

We awoke the morning of July 15. At Newcastle the weather was a bit stinking but we were briefed on the complete mission which was to take us from New Castle up to the Arctic Circle then down to Preswick, Scotland, our destination. Our first stop after Newcastle was to be Presque Isle, Maine, but the weather was closed in above the State of New York. Partridge asked for permission to land at Mitchell Field, New York. He received an OK to the delight of the whole crew especially Mac (Lt. C. W. McKenna—co-pilot) who is a resident of Brooklyn and proud of it.

The trip to New York from New Castle took us about forty minutes. We were on course at Newcastle for New York at 1216 hours and we arrived over Mitchell Field at 1250 hours. We landed, gassed up and checked the weather, and we were delighted to find the weather stinking at Presque Isle. We were all set for a night in the city of cities. Partridge and I were fresh out of tropical sun tans so we had to go into our bags and break out our winter uniforms, pink & greens, because we were letting nothing stand in our way: we were going to spend an evening in New York.

As things progressed, however, we saw very little of New York. Diaz (S/Sgt. A.C. Diaz of New Jersey) lined dates up for Partridge and myself and we dined and danced and had a few drinks of course. The girl I was with was named Ethel Roth and she was older than I but full of fun and I was told that she was quite well to do. I missed June very much here as I have on many such occasions. When I finally turned in it was 0400 hours on July 16. Due to a slip up of times we missed Mac and his sister in the Hotel Commadore and I missed meeting his sister.

We all arrived at the Field, which is about an hour's ride via tram from downtown New York, at about 0930 hours and though we were a bit tired we decided we had better get along to Presque Isle, Me. We checked the ship and found some minor difficulties—I don't recall just what they were, anyway, we were a few hours before talking off. It was this delay that was responsible for us having an extra passenger aboard on the trip north. He was a dentist stationed at Mitchell or nearby and his home was in the vicinity of Presque Isle. He told Partridge his story and although we were already over loaded Partridge agreed to let him go with us. I don't remember his name which was undoubtedly of Polish origin. He was a Captain however and he had never been aloft in a flying machine of any kind before. I must say he picked a ship for his first ride.

We had lunch at the PX and I didn't know it at the time but the meal was to be the best I would see for some time. We then went to the ship. I instructed our passenger in how to buckle on a chute and also where he would go out in case we were forced to abandon ship.

At exactly 1500 hours we roared down the runways at Mitchell and Partridge had to jerk our ship off the runway and we missed some high tension lines at the edge of the Field by inches. #1863 had come through for us as the champion she was.

(As for the navigation on the trip from Newcastle-Prestwick, it is covered in my log which I have enclosed. The purpose of this entry is to record some of the many things that happened that I was unable to put in my log.)

We were cleared from Mitchell by airways which means we were to follow the route of the transports and under control of C.A.A. We were to check in at each station as we flew over them. Our first check in point was Hartford, Conn. and we entered New England. The weather was clear and we got a good look at the countryside. It was beautiful and our eyes bugged out of every opening in the ship. The Capt., although a bit nervous, was enjoying himself, I could see that. We then checked in at Boston (home of Engineer S/Sgt. F.W. Becker [3] and then turned up the coast toward Portland, Me. and we took a good look at Boston and its famous Harbour. The Atlantic was a beautiful blue green as it washed the "rock-bound coast" past Portland, then Bangor and into the hill country of Maine. The mountains were on our left but we flew over some large hills. The country as a whole was beautiful and we all filled our eyes with it. We arrived at Presque Isle at 1731 hours and Partridge made a beautiful landing and the Capt. was thrilled beyond words. He shook hands with the crew and expressed his thanks over and over again and he suggested a name for our ship. He said we should call it Ex Caliber (Sp??) which I believe was the name of King Arthur's sword. We never did get around to naming 1863; it was just as well I guess.

August 24 — Story of first Atlantic Crossing, cont.

And so the night of July 16 found us at Presque Isle Air Base, headquarters for the North Atlantic Wing of the A.T.C. We were processed immediately and given quarters. We reported a few minor defaults in our ship and the ground crews began work that night.

We were briefed the following morning on the remainder of our route. I was also given a complete set of maps. It was a well planned trip in every detail, obviously the product of long experience and many crossings made over the same route. All course lines were laid out and marked in sections with the distances printed on course lines. Due to great changes of variation over short distances in those high latitudes our headings were changed at intervals all along the route [4]. Back to the A.T.C.: most of its personnel is made up of former Air Line pilots & crews. They are very capable and are doing a damn good job. We were briefed long and thoroughly on emergency procedures especially. Every little safety gadget known was placed at our disposal from tiny parachute first aid kits to 7-men dinghies. To get aircraft across quickly & safely is the A.T.C.'s foremost purpose.

We spent eight days in Presque Isle before we were able to get off. Weather was the main reason for this: we would have left 3 days earlier, however, but we had to have more work done on our ship the morning that the weather would have allowed our going.

We spent eight days in Presque Isle before we were able to get off. Weather was the main reason for this: we would have left 3 days earlier, however, but we had to have more work done on our ship the morning that the weather would have allowed our going.

We went into Presque Isle a few times. It was a small but friendly little town. The New England nights were pretty but a little cool for July. The moon was big and bright each night and we took a few moonlight taxi rides to some of the nearby towns. I went to one dance while I was there with a Miss Benjamin. I don't remember much about her: In fact I probably would not recognize her if she was standing before me now. I was pleased with New England and I tried to imagine what the country-side would look like in December under that same moon. The people were very friendly toward us and we enjoyed a slow but not dull time at Presque Isle.

On the 24th we awoke on what seemed to be just another day. We didn't know that it was on this day we would leave the United States for how long only time will tell. We left Presque Isle on course for Goose Bay Labrador. 1863 rose like the queen she is above the hills of Maine and we pointed her nose north. We were on course over the field at 1439 hours. At 1511½ we passed over Cambellton on Baise de Chaleur on course and at 1539 we passed over the Gulf of St. Lawrence and on the Northern shore we passed over our last check point, Mingan, a small airdrome. From there until we sighted Goose Bay we saw nothing below us but rivers, forests, and mountains, almost all of them failing to appear on our maps. We did straight D.R. from Mingan on to our Destination and we came out very well. We landed at Goose Bay's beautiful and very adequate landing field and airdrome. We, at least I, set foot on the King's soil for the first time that afternoon. We made the run from Presque Isle to Goose Bay, a distance of 568 miles, in two hours and thirty minutes flat. #1863 performed like a dream.

Even in July Goose Bay was a bleak place; there were scattered showers in all quadrants when we set 1863 down on the new and very good runway. There was a high overcast above the thunderclouds which gave the place an even darker and, I must say, drearier atmosphere.

We talked that afternoon to men, Americans who had been stationed there in Labrador for a number of months. We saw pictures on the walls of scenes showing the airdrome in December. Deep snows that lay [5] high as late as March and April. As it was on that day in July, however, there was no snow and it wasn't too cold but we wore our jackets as we did in Presque Isle.

After supper and a friendly game of poker at the Officer's Club we retired to our rooms for a good nights sleep. Oh yes! I mustn't forget the Scotch—we did have a few drinks of good Canadian Scotch during the course of the evening.

We awoke the next morning. (I almost forgot something else. We drew straws to see which of us had to sleep with the ship that night as there were no guards at the base and the planes had to be under guard at all times. I lost.) So the next morning I awoke in the plane. My bed was made up of a series of cushions laid end to end from the co-pilot's seat to the nose of the ship. There was plenty of clothing in the ship for cover and I was very comfortable in the good old ship with the rain coming down outside. Again I repeat, we awoke, me at the three o'clock, and I walked down to the room and got the other boys up at

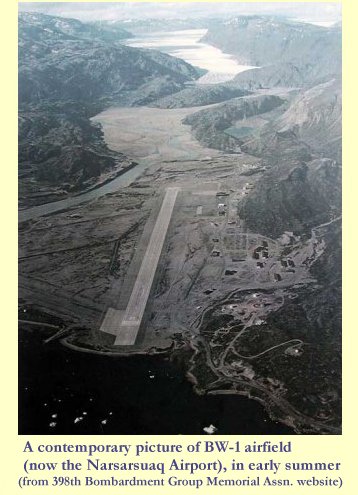

4:00. (It was daylight at three.) We were briefed at about eight hours (G.C.T.) and I made out the flight plan while both pilots watched motion pictures of a plane on the approach to Blue West One (BW-1) in Greenland.[6] We waited for the weather ship to bring in the data on the route weather.

4:00. (It was daylight at three.) We were briefed at about eight hours (G.C.T.) and I made out the flight plan while both pilots watched motion pictures of a plane on the approach to Blue West One (BW-1) in Greenland.[6] We waited for the weather ship to bring in the data on the route weather.

We were finally on course for BW-1 at 1651 (G.C.T.) on July 25. There was quite a bit of weather around the field and we were forced to fly very low until we reached the coast. We crossed the coast at 1729 hours and found ourselves on course over the Davis Straights. It was here that I saw my first iceberg. There were quite of few of them in the cold water below us.

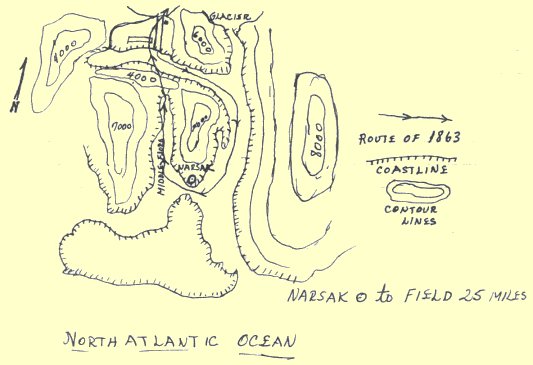

The weather on this leg was the best we encountered on the whole trip. When we were still some 100 miles out of destination the mountains of Greenland were spotted on the horizon. It was a thrill to look out and see them through the haze— that was Greenland ahead, Greenland almost on top of the world. As we passed over the radio tower at BW-3 at 2008 we spotted our Fjord, the one we were to follow through the mountains to BW-1. We were in the Fjord (canyon) for some 15 minutes, past the little Eskimo village of Narsak and then around the mountain. And there was our field over there. We circled to the left and let down and we glided to a smooth landing on an iron mesh landing strip. We were in Greenland, three down and two to go.

In the land where there is no night we spent two days. We slept in blacked-out barracks, not to keep light in but to keep it out. BW-1 as the airdrome is called is situated on a Fjord that is fed by a glacier that is just above the field itself. It is surrounded by mountains; all I would say were at least 5,000 ft. or better. There were much higher mountains in the distance.

We tramped around the hills and climbed the mountain that was directly behind our barracks. The place did things to you with all its rugged beauty. It gave you the feeling of strength and I immediately put it on my list of places I hope to see again in peace time.

September 4 — England

We left Blue West #1 and the land of ice and the mid-night sun on July 27. We took off after the weather briefing and 1863 was in the air #3 at 1332 (G.C.T.). We flew down the Fjord to the Eskimo town of Narsak and turned right and came back up the middle Fjord to the field as shown below. (From memory please forgive)

We were on course to Meeks Field Iceland at 1353. We had decided at the briefing to fly over the ice cap instead of going back to the sea and following the coastline around. This second alternative would have been some 124 miles out of our way. We found the weather on the cap clear as a bell and the sun was so bright we were forced to put on our special sun glasses. The cap was a site to behold. Ice as white as can be just as far as the eye could see. Flying over ice and snow is very deceptive. It is almost impossible to judge your height by sight. At 500 ft. or 10,000 ft. it all looks the same. We were told of cases of aircraft actually sliding in on the cap due to instrument failure and the eye failing to judge how far the plane was above the ice. Therefore we flew at 11000 ft. which is at least 2000 ft. above the highest known point on the cap. From the time we left the field we could see the coastline in the far distance and we finally crossed it at 1424 hours. The coastline was a wall of ice and it is here in the spring of the year that the iceberg is born. We could see many bergs along the coast north to south.

We were on course to Meeks Field Iceland at 1353. We had decided at the briefing to fly over the ice cap instead of going back to the sea and following the coastline around. This second alternative would have been some 124 miles out of our way. We found the weather on the cap clear as a bell and the sun was so bright we were forced to put on our special sun glasses. The cap was a site to behold. Ice as white as can be just as far as the eye could see. Flying over ice and snow is very deceptive. It is almost impossible to judge your height by sight. At 500 ft. or 10,000 ft. it all looks the same. We were told of cases of aircraft actually sliding in on the cap due to instrument failure and the eye failing to judge how far the plane was above the ice. Therefore we flew at 11000 ft. which is at least 2000 ft. above the highest known point on the cap. From the time we left the field we could see the coastline in the far distance and we finally crossed it at 1424 hours. The coastline was a wall of ice and it is here in the spring of the year that the iceberg is born. We could see many bergs along the coast north to south.

We had clear weather and good visibility until 1553, at that point (63°28´ N 32°00´ W) we ran into a cloud bank and we began to climb to get over it. According to Metro we could top anything at 14000. We reached 14000 and we were still in it; rime ice began to form on our wings and we were completely without deicer equipment. The ice seemed to melt away rapidly and we didn't worry so much about the ice. Our chief worry was that we were at 15500 without sufficient oxygen equipment. At 15,800 ft. we broke out into the blue and warm sunshine. We had three oxygen bottles in front, one in tail. Tail gunner Mills kept the one in the tail. We set aside one of the bottles in front for the pilot. The R/O, Co-Pilot, Eng. and I used the other two. We just gulped down a few breaths every now and then taking it through the mouth. At 1623 we were able to come back down to 8,000 and we put the oxygen up.

At 1704 we sited the coast of Iceland and we started our glide in. It looked cold and bleak down there and there was a wind of some thirty-five miles per hr. blowing. We were the first of our group to land in Iceland.

(To be continued)

Unfortunately, Billy never did continue the story of his Atlantic Crossing. We have the bare details recorded in the navigator's log to tell us that they arrived in Meeks Field, Iceland on July 27 at shortly after 5 p.m. They took off from Meeks in the morning two days later. There is a page in the log that seems to indicate a brief stop in Stornoway, Scotland (appropriately enough on the Isle of Lewis off the Scottish mainland) but the plane might not have actually landed there. Perhaps they merely checked in with British officials as their first contact with the U.K. At any rate, they landed in Prestwick, Scotland, shortly after noon on July 29. We also know that the successful crossing gave him the confidence in his navigational skills that he would need to overcome some early mistakes in navigating during bombing missions (see his November 17, 1943 Journal entry).

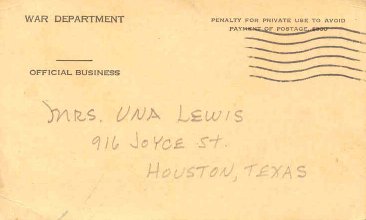

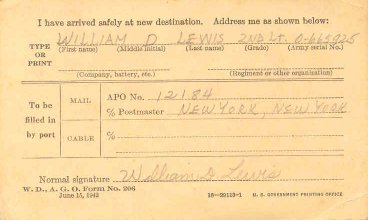

Of course we know he arrived safely, but here is the welcome official word that his mother received from him through the Army, giving her his new address, which does not disclose his actual location in the E.T.O.:

|

|

[1] In addition to Dr. McKenna's widow, with whom I have been in contact and who has lent me numerous pictures and provided a lot of information for inclusion in the Journal, I have also been in contact with relatives of Mr. Partridge, who was killed in Korea in 1952. To see more about him, click here.

[2] For more information on the routes taken by Marauders on their way to Europe, see this page which includes a map of Billy's crossing route.

[3] There are some snapshots of Sgt. Becker, as well as Lts. Partridge and McKenna, on the Journal Hiatus page.

[4] The meaning of this sentence is not clear to me, but I suspect he is referring to magnetic variations.

[5] This is one of the few words in the entire journal that I simply could not make out, but "lay" fits the sense of the sentence, I believe.

[6] The airfield at BW-1 is now an airport, Narsarsuaq, serving southern Greenland. We think Billy visited, or at least flew over, this site after the war; click here to see some pictures of the site, and more information about it.

Forward to Fall, 1943 |